Table of Contents

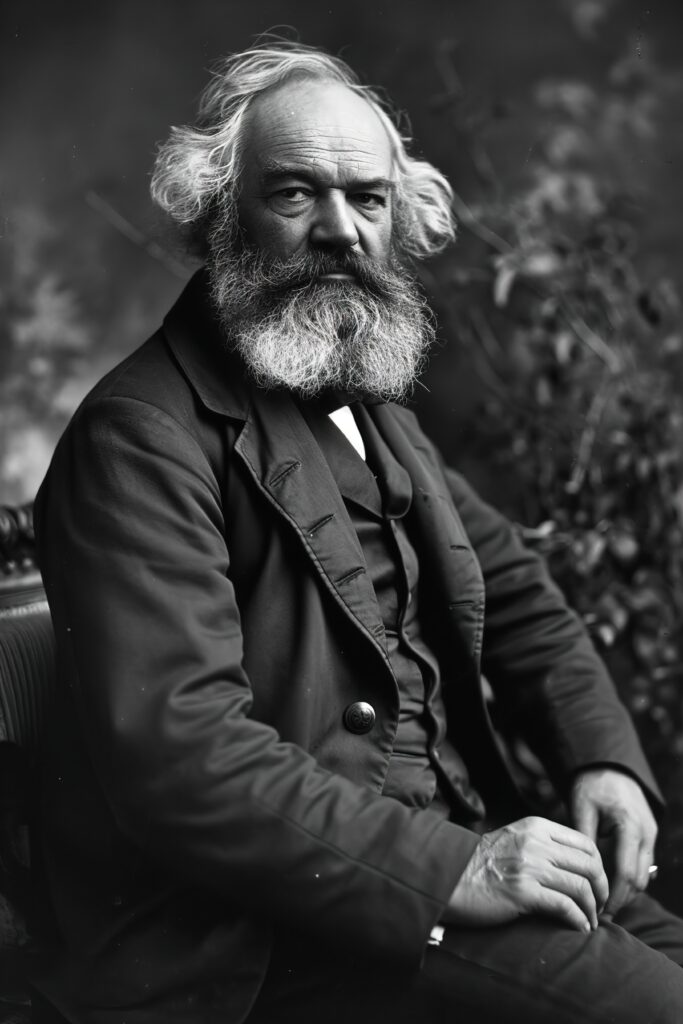

Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism, articulated most comprehensively in Das Kapital, remains one of the most influential economic theories in history. At its heart lies a powerful indictment: profit represents exploitation. According to Marx, capitalists extract surplus value from workers by paying them less than the value they create, pocketing the difference as profit.

This analysis has shaped political movements, inspired revolutions, and continues to inform contemporary critiques of capitalism. Yet for all its intellectual force, Marx’s theory fundamentally misunderstands the nature of entrepreneurship and the legitimate sources of profit in a market economy.

The problem isn’t that Marx was entirely wrong about the existence of exploitation in 19th-century factories—such abuses were real and widespread. Rather, his error lies in reducing all profit to exploitation, thereby failing to recognize what entrepreneurs actually do.

Marx’s Theory: Profit as Surplus Value

To understand where Marx went wrong, we must first understand his argument. Marx built upon the classical labor theory of value, which held that the economic value of a good derives from the labor required to produce it. In Marx’s formulation, workers create value through their labor, but capitalists—who own the means of production—pay workers only a subsistence wage while appropriating the surplus value for themselves as profit. This surplus value, Marx argued, represents unpaid labor.

If a worker creates $100 worth of value in a day but receives only $40 in wages, the capitalist has essentially stolen $60 of labor. The capitalist contributes nothing to production except legal ownership of capital, which itself represents the accumulated surplus value extracted from previous workers. Profit, in this view, is not earned but taken—it is the mechanism by which one class exploits another.

Marx saw the capitalist as essentially a parasite, someone who inserts himself between workers and the products of their labor, extracting rent merely for possessing legal title to factories and machines. The capitalist’s role is purely extractive, not productive. This analysis led Marx to conclude that a more just economic system would eliminate private ownership of capital, allowing workers to retain the full value of their labor.

The Entrepreneurial Functions Karl Marx Overlooked

Marx’s analysis suffers from a critical blind spot: it fails to account for several distinct and valuable functions that entrepreneurs perform. These functions create genuine economic value, and profit serves as compensation for them. Let’s examine each in turn.

Risk and Uncertainty

The most obvious function Marx undervalued is risk-bearing. Entrepreneurs invest capital—whether their own or borrowed—with no guarantee of return. They commit resources to ventures that may fail, and indeed, most new businesses do fail. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, approximately 20% of new businesses fail within the first year, and about 50% don’t survive past five years.

This isn’t merely a matter of probability; it represents a real economic function. Someone must bear the risk of uncertainty in production, and that role falls to the entrepreneur. Workers receive their wages regardless of whether the enterprise ultimately succeeds or fails—their compensation is contractually guaranteed. The entrepreneur, by contrast, receives profit only if the venture succeeds, and loses their entire investment if it fails.

Marx was aware of risk but dismissed it as insignificant, arguing that capitalists possessed such vast wealth that individual losses barely affected them. This may have been true for some industrialists in Marx’s time, but it hardly applies to the broader universe of entrepreneurship. Most entrepreneurs are not wealthy magnates risking a small portion of vast fortunes; they are individuals betting their savings, their homes, and years of their lives on uncertain ventures.

The economic function of risk-bearing cannot be eliminated by changing ownership structures. In a worker cooperative, someone still must bear the risk of business failure. If workers collectively own the enterprise, they collectively bear the risk—and the potential reward. The entrepreneurial profit in a successful venture partly compensates for the losses incurred in unsuccessful ones.

Coordination and Resource Allocation

Entrepreneurs perform a crucial coordinative function that Marx’s theory struggles to recognize. Production doesn’t happen automatically when workers and raw materials come together. Someone must decide what to produce, how much to produce, which production methods to use, how to organize the division of labor, where to source materials, and how to distribute the final product.

These decisions require judgment, often under conditions of imperfect information. An entrepreneur must coordinate diverse factors of production—labor, capital, natural resources, and intermediate goods—into a productive combination. This coordination creates value beyond the sum of individual contributions.

Consider a simple example: three workers might have skills in carpentry, metalworking, and upholstery, respectively. Individually, they can each create items of modest value. But an entrepreneur who recognizes how to combine their skills to produce high-quality furniture creates value through coordination. The resulting furniture may be worth far more than the sum of what each worker could produce independently. The entrepreneur’s insight about how to combine these factors productively is itself a form of value creation.

Marx might respond that workers could coordinate themselves democratically, eliminating the need for a separate entrepreneurial class. And indeed, some successful cooperatives demonstrate that this is sometimes possible. But democratic coordination carries its own costs—decision-making time, potential for disagreement, and the challenge of collective action when interests diverge.

Innovation and Creative Destruction

Perhaps Marx’s greatest oversight concerns innovation. Entrepreneurs are the primary agents of what economist Joseph Schumpeter later called “creative destruction“—the process by which new products, production methods, and organizational forms replace old ones, driving economic progress.

Entrepreneurs innovate by introducing new goods, developing new production techniques, opening new markets, discovering new sources of supply, or creating new organizational structures. These innovations create value in ways that routine labor does not.

The entrepreneur who first recognizes that a new technology can be applied to solve an existing problem, or that consumers will value a product that doesn’t yet exist, creates genuine economic value through this insight and initiative.

Marx’s theory, focused on the production of existing commodities using established methods, has difficulty accounting for this dynamic aspect of capitalism. The labor theory of value works (if at all) only in a static world where everyone knows how to produce existing goods. It breaks down entirely when confronting the question of how value is created through innovation.

Consider the smartphone. Workers certainly labored to produce the components and assemble the devices. But the extraordinary value of smartphones—the reason they command premium prices—lies not primarily in the labor of assembly but in the innovative design, the development of user interfaces, the creation of app ecosystems, and the insight that consumers would value mobile computing. These innovations were entrepreneurial achievements, and the profits they generated represent compensation for creating something genuinely new and valuable.

Time Preference and Capital Accumulation

Marx also failed to adequately account for time preference—the fact that people generally prefer present consumption to future consumption. When an entrepreneur invests capital in a business venture, they forgo present consumption in favor of potential future returns. This deferral of gratification is itself an economic contribution.

Capital accumulation requires that someone save rather than consume. The machinery, factories, and equipment that workers use to increase their productivity exist only because someone previously chose investment over consumption. While Marx recognized that capital increases labor productivity, he characterized all capital as dead labor—previous surplus value extracted from workers. He failed to see that the decision to accumulate capital, rather than consume wealth, creates value by enabling future production.

Interest on capital—which Marx condemned alongside profit—partially compensates for this time preference. Similarly, entrepreneurial profit rewards those who commit resources for extended periods without guarantee of return. A business might take years to become profitable, during which the entrepreneur’s capital is locked up and unavailable for other uses. The eventual profit, if it comes, compensates for this opportunity cost.

Information Discovery

Twentieth-century economists, particularly those in the Austrian school tradition, identified another crucial entrepreneurial function that Marx missed entirely: the discovery and processing of information dispersed throughout the economy.

Friedrich Hayek argued that the economic problem facing society is not merely the allocation of given resources to known ends—the kind of mechanical calculation that Marx’s central planning might handle. Rather, the challenge is that knowledge about resources, needs, opportunities, and preferences is dispersed among millions of individuals, constantly changing, and often tacit rather than explicit.

Entrepreneurs serve as information processors in this complex system. They identify opportunities that others have missed—noticing that resources are being underutilized here, that demand exists for something new there, that a production method could be improved in this way.

Profit signals successful information discovery; loss signals mistakes. This function cannot be eliminated by changing ownership structures or through central planning, because the information entrepreneurs discover often exists nowhere until they discover it through market experimentation.

An entrepreneur who recognizes that lumber in one region could be more valuable if transported and sold in another region creates value through this information discovery. The profit earned reflects the value created by moving resources to higher-valued uses. Marx’s framework, focused on exploitation within existing production processes, cannot account for the value created by reconfiguring how resources are used.

The Empirical Problem: Where Marx’s Predictions Failed

If profit were simply exploitation—payment for nothing—we would expect certain empirical patterns that we don’t actually observe. First, we’d expect profit rates to be relatively uniform across industries, reflecting the uniform exploitation of labor. Instead, profit rates vary dramatically across industries and firms, suggesting that profit relates to factors other than mere ownership of capital.

Second, we’d expect industries with similar capital intensity to show similar profit rates. They don’t. Some capital-intensive industries are highly profitable; others barely break even. This variation suggests that profit depends on factors like innovation, efficiency, and market positioning—entrepreneurial variables—rather than simply the ratio of capital to labor.

Third, we’d expect that as capitalism matured, profit rates would decline (as Marx indeed predicted), since competition would force capitalists to share more of the surplus value with workers. Instead, profit rates have remained relatively stable in developed economies, while workers’ real wages have increased dramatically—precisely the opposite of Marx’s predicted immiseration of the working class.

Finally, we observe that entrepreneurial economies generate far more prosperity than planned economies. If entrepreneurial profit were merely extracted surplus value, eliminating entrepreneurs shouldn’t reduce productivity. The dismal economic performance of socialist economies suggests that the entrepreneurial function is indeed productive, and that profit serves as compensation for real value creation.

Exploitation Without Entrepreneurs?

None of this denies that exploitation exists or can exist in capitalist systems. Workers can be underpaid, subjected to dangerous conditions, denied bargaining power, or otherwise treated unjustly. Marx was right to identify and condemn such practices. However, his error was in concluding that all profit necessarily represents exploitation and that the entrepreneurial function contributes nothing of value.

The existence of genuine entrepreneurial value creation doesn’t mean that every dollar of profit is legitimately earned. Profit can derive from multiple sources: genuine value creation through entrepreneurship, but also market power, regulatory capture, rent-seeking, fraud, or yes, exploitation of workers.

The challenge for economic justice is to distinguish legitimate from illegitimate profit, not to condemn all profit as inherently exploitative. Marx’s all-or-nothing approach—profit is entirely exploitation—led him to an erroneous conclusion: eliminate private capital ownership and profit, and you eliminate exploitation while retaining productive efficiency.

The 20th-century experiments with this prescription revealed the flaw. Without the incentive structure that profit provides, entrepreneurial functions aren’t performed effectively. Resources are misallocated, innovation stagnates, and efficiency suffers.

A More Nuanced Understanding

A mature understanding of profit recognizes multiple components. Some profit represents return to risk-bearing. Some compensates for the opportunity cost of capital. Some rewards successful innovation. Some reflects superior coordination and management. Some derives from monopoly power or other market imperfections. And yes, some may represent underpayment of workers relative to their productivity.

We might also rethink how entrepreneurial functions are organized. Worker cooperatives, profit-sharing arrangements, and employee stock ownership plans allow workers to participate more fully in entrepreneurial returns while still preserving incentives for risk-taking, innovation, and effective coordination.

These hybrid forms recognize both Marx’s concern for workers’ welfare and the genuine economic functions that entrepreneurship performs. Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism identified real injustices in the industrial system of his time. His moral passion for workers’ welfare and his systematic analysis of capitalist dynamics commanded admiration even from those who disagreed with his conclusions. But his reduction of all profit to exploitation reflected a fundamental misunderstanding of entrepreneurship.

The challenge for modern economies is not to eliminate entrepreneurship and profit, as Marx recommended, but to structure institutions so that profit derives from genuine value creation. This requires moving beyond Marx’s framework to a more nuanced understanding. Marx asked the right questions about capitalism’s moral foundations. But by misunderstanding the nature of entrepreneurship, he arrived at the wrong answers—and the societies that implemented those answers paid dearly for his error.

Pingback: The 'Bullshit Job' Economy: Why Keynes Predicted We'd Invent Fake Work - intellectualprestige.com